Wes Anderson with his latest film, The French Dispatch, found himself reaching for the peaks of his singular vision, though perhaps to the detriment of all but his most ardent supporters as he left the rest of us far below.

TFD is setup much like a play might be, with a prologue, epilogue, and 3 clearly defined acts in between, each telling a distinct story though all within the artifice of a New Yorker like magazine based out of Paris, France. While unique a concept I’ve not had much positive experience truthfully with this style in films, as others like Four Rooms did not quite work for me; however, I still had hope that perhaps Anderson could use this to his advantage.

From the jump, you see his style front and center as always, and the sequence with Anderson regular Owen Wilson proves to be a charming introduction to the city and the movie itself. However for my perspective this prologue was the last time the film would show much heart till perhaps the 3rd act.

Instead we seque from Wilson to the introduction of featured Andersonian partner, Bill Murray, leading the paper as he has for years, and – in a blink and you miss it moment – in honor of his time, three pieces will be repreinted in his honor. These stories are the ones we will be focused on for majority of the film.

Story one to me is the one that will really prove if you love or loathe this effort. In it you meet Guillermo Del Toro playing quite ably an artist who is in the penal system and is making the most abstract figure art with his muse/lover/jailer played by Seouyx. To his fortune, or misfortune as you may determine, he encounters an art collector and salesmen played by Adrien Brody. Brody merely has to play smarmy, and he does this quite well, as he sweeps up Toro’s art into a frenzy and gives it life beyond all expectations by using his sales talents and leaning into the farce that is so often already surface level – the art market (recently sent up in such films as The Room).

This sequence of the three had perhaps some of Anderson’s greatest attempts at humor, largely with the premise of laughter at the unexpected. However, even as a non-Andersonian fanboy who’s not seen all his works, these landed dully for me as I often expect he most unexpected and thus even the zaniest elements seemed obvious.

Likewise I was put off, and this may be me personally, by what appeared to be the ever present male gaze with how Seydoux herself was presented in the sequences. I didn’t find the art scenes all that necessary, and even if the joke were to show how abstract and contrasting the art itself was from the figure of her body, I think this could have been achieved in otherways that were less grimy.

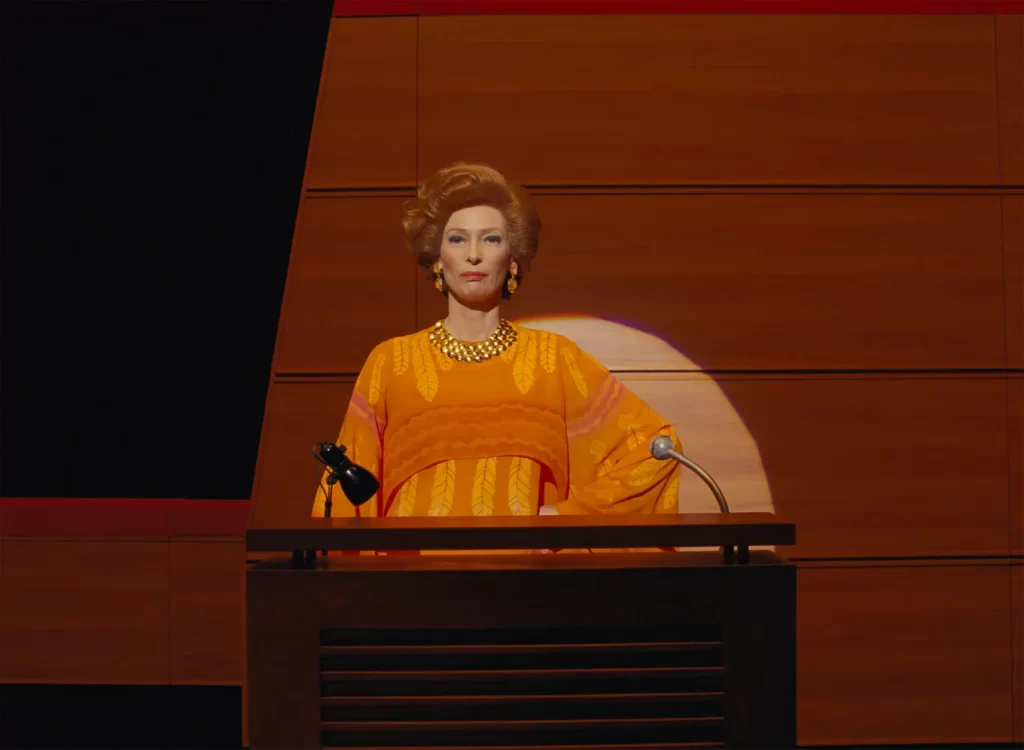

I forgot to mention that this was truly a story in a story, as all three stories are, told in this case by Tilda Swinton, the writer, delivering what comes across as perhaps the strangest TED talk one would ever seen. Tilda’s character was most reminiscent to me of her portrayal in Hail Caesar. While I can’t say I particularly loved the character, I thought Tilda did a wonderful job pulling said character off.

In no time we move on to scene two where Francis McDormand relays the tale of her time with a youth uprising in France, where the characitarures all around are in rare form, with Timothee Chalamet leading the charge as one of Anderson’s newest cast members.

McDormand struggles here with her sense of journalistic perspective, as she goes from an embedded reporter, to a reporter in bed, to the writer of the manifesto the students themselves want to deliver. Though I still do not know how I feel overall of the relationship between her character and Timothee, I feel it’s perhaps to Anderson’s credit that McDormand’s age isn’t played for laughs but instead is a natural divide for her and Timothee when one considers the movement he has partaken in is a youth movement. This especially comes to a head as an initial foil of his is setup as a likewise eventual romantic partner.

Aside from one scene in particular though, where a protest meets a chess match meets a riot, I wasn’t left with much of an impression from this act, and perhaps would consider it one of the weaker elements overall, even as I wasn’t particularly fond of the first act.

Lastly we come to the much anticipated inclusion of Jeffrey Wright, also a new Andersonian cast member, in the role of a food critic inspired loosely by the late great James Baldwin. Of the writers Anderson pays tribute I was most familiar with Baldwin; however, Jeffrey Wright I really had not seen in anything significant in sometime, as I’ve not partaken of Westworld.

I immediately realized why you cast someone like Jeffrey Wright, as his commitment to both the Anderson archetype, and his own charisma onscreen, worked well to give the movie another shot at much needed heart.

Wright in a segment as amusing, if not more so, than Swinton’s TED talk, is on a late night program and recounts verbatim the story of the story that is included in this last issue. This begins with his personal connection to Murray’s character, and follows with Wright’s covering of a kidnapping. What might this have to do with cooking you might say – as Murray’s character himself does – but I’d argue without this angle, you might also be left to wonder why tell this story of the kidnapping at all, as perhaps for me I’ve realized it’s the most forgettable of the three, so for the framing device to include Wright I am quite thankful.

After Wright’s sequence, we are provided the epilogue which is truly a coda for the film, and thus little of the unexpected occurs and instead Anderson attempts to tie a bow around what is at this point a rather fat package of unique and uniquely odd stories. However tight that bow fits might be for you to determine for yourself.

I will conclude by saying where a fan of this film might see an opportunity for a rewatch to mine the plombs of Anderson’s intricate details and well-planned scenes, I cannot see myself revisiting this film unless to perhaps down the road compare this to one of Anderson’s later efforts. I would say it’s true for my biases I am often hit and miss with Anderson’s films, and thus perhaps his charms as they were only work in certain films “Grand Budapest” most certainly, Rushmore not at all, so keep that in mind. Yet all that to say I certainly an not, and will not be alone, in questioning if Anderson should perhaps indeed curtail his impulses to find the heart of the story once more, though whether he shall in future releases is yet to be seen.