Ten years ago with the release of Hayao Miyazaki’s ‘The Wind Rises’, Miyazaki announced his retirement from filmmaking. Perhaps Miyazaki felt that this semi-biographical tale of Jiro Horikoshi was to be the perfect finale for his career, as it reflected more than perhaps any film Miyazaki’s own personal story, as a son of a World War II aeronautical engineer. If that’s the case then perhaps Miyazaki still thought there was more to be said, as he returned from retirement a few years ago to begin work on ‘The Boy and the Heron’, a deeply strange, yet increasingly personal film that is perhaps Miyazaki’s most layered, abstract film to date, even as it touches on key themes of family, loss, and change.

In ‘The Boy and the Heron’, we are taken to Tokyo in the middle of WWII and introduced to a young boy named Mahito Maki, who has just been told his mother’s hospital has caught on fire. In the distance a pyre hundreds feet high already burns, yet he bursts out of his house in a vain attempt to save her, though it is too late. A year later after her death, Mahito is now being taken from Tokyo to the countryside by his father. Mahito’s father introduces his son to Natsuko, who quickly relays to Mahito that she’s to be his new mother and she’s carrying his father’s next child. Left in her care in a countryside villa, Mahito is largely left alone. The kids at school bullied him, and even the Grey heron, acting increasingly strange in his company, seems to have it out for him. Mahito tries to hunt the heron unsuccessfully, though in doing so he discovers a strange tower connected to his family. One day he witnesses Natsuko disappear into the woods, and to save her, and perhaps his mother as well, he enters the tower whereupon a strange wondrous world awaits with danger, adventure, and perhaps answers.

Miyazaki himself was a very young boy during the end of World War II, whose early memories are tied to those desctructive days, and undoubtedly he’s channeled a part of his childhood into Mahito. Miyazaki afterall certainly took much of his love of flying contraptions and machines from his youth, and so to see fuselages as Mahito does would likely mirror Miyazaki’s experience. Miyazaki too lost his mother, thought not as early, and it’s said she is seen in many of his characters throughout his films. So no doubt there’s a personal touch in the early scenes for sure. Once Miyazaki takes Mahito in the tower however, we begin a surreal trek into a life that increasingly is unmoored from ties of reality, as his protagnoist struggles to understand loss, life, and family.

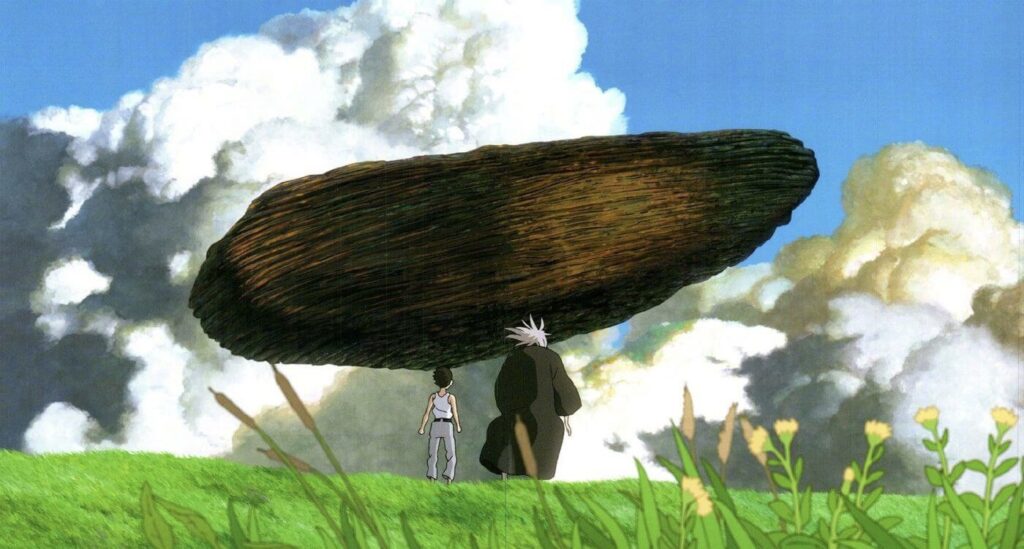

The Boy and the Heron (Source: GKIDS)

Unlike most of Miyazaki’s earlier films which however strange seem to have a clear throughline, ‘The Boy and the Heron’ doesn’t attempt to give easy answers and instead seems to present mood pieces to contemplate on well after the credits. In fact this film has more in common with Andrei Tarkovsky ‘s Stalker or Dante’s Divine Comedy. In which case, the Heron serves as Mahito’s Virgil through this strange journey, whereupon he meets alternate versions of characters, as well as some truly wild creations such as an army of destructive parakeets. And as in Stalker, Mahito’s being guided to a world unknown but filled with the promise of a desire fulfilled, which he hopes would be the return of his mom.

Does Mahito find what he seeks at the end of his journey or just what he needs? This perhaps may be a more clear question and answer; however, that cannot be said for many of the film’s posits, as it’s truly a dense journey that requires possibly several rewatches. While I delight in Miyazaki’s films, especially rewatching them, this is perhaps the first that requires those revisits, which is why I felt some distance from the film. It almost feels too soon then to write this review, knowing I’m surely missing more, because though I enjoyed the ride I was also left feeling perplexed. So while I surely do not know the answers, I can still say I enjoyed the strong visuals, the boldness of Miyazaki’s choices, and even as I’m working to secure myself deeper into the film I know Miyazaki is nothing if not precise with his directing, and so I look forward to unlocking its secrets more fully one day. Perhaps ‘The Boy and the Heron’ will blend into Miyazaki’s ouvre with time, or perhaps it will stand singularly apart, even more so than ‘The Wind Rises’ before it. It’s hard to say, but even if it’s not his last film – as he’s unretired it seems once again – it’ll be an unforgetable part of his legacy.

The Boy and the Heron (Source: GKIDS)