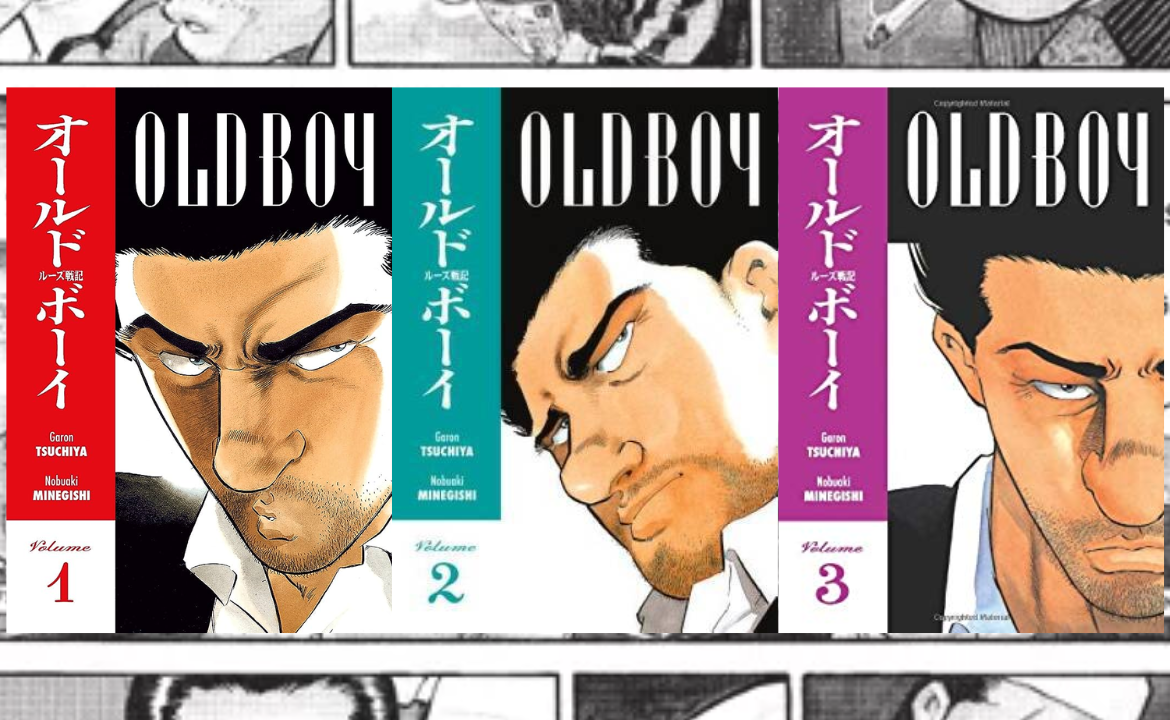

On the 20th anniversary of Park Chan-wook’s ‘Old Boy’, we thought it appropriate to share our review of the original manga series that inspired the film.

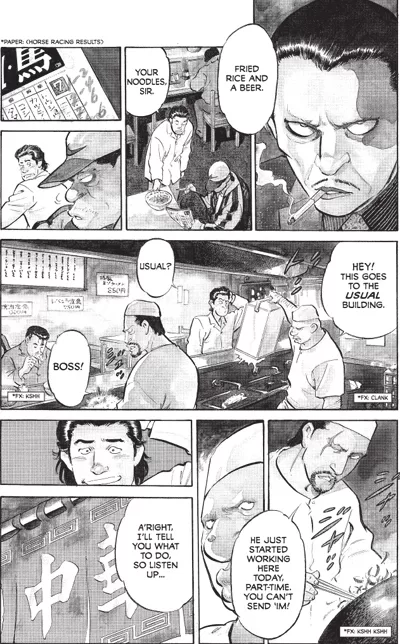

For most of his youth, Shinichi Goto led a life with no extraordinary purpose and no clear future in mind; however, that all changes one day when Goto is suddenly kidnapped, locked away, and kept in solitary confinement given only food, tv, and weights to entertain him. After ten years pass Goto is released just as mysteriously as he was captured and is told only that someone with a great hatred towards him payed an exorbitant amount of money to have him held in the cell. Goto uses limited information about his time in prison to seek revenge on the person who stole ten years of his life from him. In his quest for revenge, Goto makes unlikely friends, meets cunning enemies, and all the while delves deeper into the ‘game’ he unwillingly joined.

I first heard of Old Boy the manga after purchasing the Korean film adaptation that has now become a classic of cinema and helped herald a new wave of Korean cinema. The story for both the film and manga intrigued me not solely because it’s a revenge story, but because of the nature of Goto’s mysterious imprisonment. To have someone hate another person so much that they’d pay to take away ten years of their life is indeed unique and horrid all the while. Of course, the character Edmond Dantes perhaps had an even worse fate awaiting him in my favorite novel Count of Monte Cristo, as he was supposed to be locked away till death; however, in the Count of Monte Cristo much is known about Dantes’ capture and captors, thus allowing the Count to exact a slow revenge. In the story of ‘Old Boy’, little is known to Goto nor the reader about his capture. Throughout the series Goto’s search for truth often takes precedence over any acts of revenge, since he often has little information on who to retaliate against.

While The Count of Monte Cristo has many supporting characters on both sides of the conflict, ‘Old Boy’ has a narrower set of characters, which helps to intensify their purpose and additionally simplify the narrative. For the reader this also tends to enhance the mystery behind each character, especially since Goto’s knowledge of even his few friends is limited, and one never knows what might be lurking behind the veil of a friendly smile. Extensive and in-depth series such as Naoki Urasawa’s Monster, which revels in Hitchcock levels of suspense, achieves all this mystery with an overabundance of characters. Nobuaki Minegishi, the mangaka for Old Boy, seemed to prefer a more traditional Film Noir style. While I love Monster and many of Urasawa’s works I think that Minegishi knew what worked for him and what he was trying to portray, and for that I have no complaints.

While not nearly as action packed or violent as many revenge thrillers can be, and as the film certainly is, Minegishi ‘s ‘Old Boy’ delivers a quality story of suspense and surprisingly familiar emotions. Indeed Goto’s search for revenge may not garner much empathy, since few can relate to his tragedy, but his attempts to redefine and repurpose his life and identity after a severe crisis are certainly not foreign concepts. Therefore while rooting for Goto to find his captor, ‘Old Boy’ transcends the traditional cat-and-mouse tale by allowing us to feel hope in the end that, regardless of his success or failure, Goto can at least return to a full life.

Of course, to know what happens to Goto you’ll have to read Old Boy, and if you like suspense, tales of revenge, and identity quests, then I’d strongly recommend Old Boy.